As we approach Christmas, I had a photo from 2014 pop up on my Facebook Memories feed: the tabletop tree at my house in Michigan, with presents stacked around it for the grandchildren, is a sharp contrast to my skinny pencil tree in my park model in Arizona. I love having this tall skinny tree after six years living in a 35-foot motor home with no room for a tree.

My tree this year is not laden with gifts. I miss the fun of wrapping all those gifts, stuffing the stockings, and watching the kids unwrap them. There is nothing as beautiful as a dark room with a lit tree and gifts below it, and nothing as fun as watching kids open those gifts on Christmas.

That made me wonder about the traditions of Christmas trees and gift-giving. The act of exchanging gifts began long before Christmas and was done during the winter solstice in ancient Rome, celebrated from December 17 to 23rd. The gifts were usually small figurines called Sigillaria, made of wax or pottery and designed to resemble gods or demigods. Then, during the new year celebrations, the Romans gave gifts of laurel twigs, gilded coins, and nuts in honor of the goddess of health and well-being.

It was in the early 4th century AD (January 1, 301 to December 31, 400) that the gift-giving custom was linked to the biblical Magi delivering presents of gold, frankincense, and myrrh to the baby Jesus. This was co-mingled with the gift-giving tradition of the 4th-century bishop, Saint Nicholas. Saint Nicholas had a habit of secretly giving gifts, and he was the inspiration for Father Christmas and Santa Claus.

In the 16th century (1501-1600), the custom of giving gifts to children developed in Europe as a way of reducing rowdiness on the streets around this time of year. Parents used it to keep children away from the streets and from becoming corrupted. These actions resulted in Christmas becoming a private, domestic holiday rather than a public holiday of carousing.

Saint Nicholas was the inspiration for the Dutch Sinterklaas, with a festival that arose during the Middle Ages. The feast was to aid people experiencing poverty, especially by putting money in their shoes. This tradition developed, and by the 19th century, it had become secularized into him delivering presents. By this time, the Santa Claus of North America had developed.

Now, the next question is, why do we place our gifts under a decorated tree? In ancient Rome, homes and temples were decorated with evergreen boughs for the winter solstice feast of Saturnalia. Celtics associated evergreens with everlasting life, and the Hebrews linked them with life and growth. In Han Dynasty China, evergreens symbolized resiliency, and the Norse people associated them with their sun god.

The Christmas tree tradition began in Germany in the 1500s. Evergreens were placed beside the medieval home’s entry, which grew into indoor trees covered with apples for the feast of Adam and Eve on December 24. The trees were also decorated with cookies and lit candles. Another tradition was the Christmas Pyramid, which was formed by wooden shelves that held Christian candles, figurines, evergreen branches, and a star.

The two traditions merged as the first decorated indoor Christmas tree. German immigrants brought the Christmas tree to the U.S. in the 1600s, but it did not become popular until the 19th century. What boosted its popularity was Prince Albert, Queen Victoria’s husband, who introduced Christmas trees to England in 1846. By the early 1900s, electricity made electric lights for trees possible, and they began decorating town squares.

Tree decorations began with simple, handmade items, and food was a popular decoration, with strings of berries, popcorn, and nuts along with cookies, marzipan, and apples. Mass production of ornaments, tinsel, beads, and “snow” batting in the 1900s developed into the intricate ornaments we see today.

The gifts under the Christmas tree began as small presents on the branches, but as the gifts grew larger and too heavy, people placed them under the tree instead.

When giving or receiving a gift, remember the spirit in which the tradition developed: a representation of the Three Kings presenting gifts to baby Jesus. That tradition has become very commercialized, with U.S. consumers expected to spend $242 billion on holiday gifts in 2025.

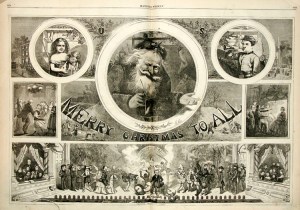

Along with tree decorating traditions, most of us grew up with the magic of Santa Clause. Saint Nicholas was a Christian holy person believed to have lived in the third century, who became known as a protector of children. The bearded, jolly Santa dressed in red that first appeared in Clement Moore’s A Visit from Saint Nicholas in 1820. Thomas Nast was an artist who’s first major depiction of Santa Claus in Harper’s Weekly in 1886 created the image we envision today. Nast contributed 33 Christmas drawings to Harper’s Weekly between 1863 to 1886, and Santa is seen or referenced in all but one. It is Nast who was instrumental in standardizing a national image of a jolly, kind and portly Santa dressed in a red, fur-trimmed suit delivering toys from his North Pole workshop.

Along with tree decorating traditions, most of us grew up with the magic of Santa Clause. Saint Nicholas was a Christian holy person believed to have lived in the third century, who became known as a protector of children. The bearded, jolly Santa dressed in red that first appeared in Clement Moore’s A Visit from Saint Nicholas in 1820. Thomas Nast was an artist who’s first major depiction of Santa Claus in Harper’s Weekly in 1886 created the image we envision today. Nast contributed 33 Christmas drawings to Harper’s Weekly between 1863 to 1886, and Santa is seen or referenced in all but one. It is Nast who was instrumental in standardizing a national image of a jolly, kind and portly Santa dressed in a red, fur-trimmed suit delivering toys from his North Pole workshop.